Southern Africa, Fall 2017

TTS30 Semester Blog

Welcome to the Fall 2017 blog- Southern Africa.

Time to Transition

We’ve now traveled thousands and thousands of miles, slept in over 30 different locations, visited four countries, and met countless people that inspired us, and taught us stories we would not be able to hear anywhere else.

Find a quiet space and get comfortable, its time to reflect and remember our semester. As students lie with their eyes closed, we asked them to visualize their answers to these (and more) questions.

When was the first time you realized that you can do things you never imagined yourself doing before? And SUCCEEDING! With flying colors? When was the second time?….12th time?

When was a time where you questioned everything you had previously learned about the world, and yourself? When did you feel yourself to quote Ali ‘shaken to your core?’ How did it feel to shed these old perceptions?

Since leaving African Leadership Academy, the group spent our last stint of the semester staying in a cozy home in the small town of Waterval Boven, a few hours outside of Johannesburg. The students focused on a variety of different projects for their finals and created a great deal of beautiful work.

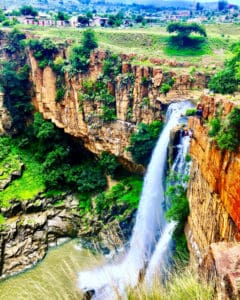

Looking to get some adrenaline flowing after classes wrapped up, we had a great day of climbing at a local crag, trying about ten different routes of varying difficulty. Our final activity consisted of testing and overcoming any nerves about abseiling (German for rappelling) as we rappelled down a 50-meter cliff next to a gorgeous waterfall. After landing safely at the bottom, each of us got the full effect of the splash as we explored behind the waterfall. Between finals and exploring the beautiful area just outside of town, we’ve found time to discuss takeaways from the semester as a whole.

Students abseiling next to a waterfall

The group after abseiling next to the waterfall

Transitioning home inevitably holds the exciting opportunity to reunite with friends and family, and also the challenge of learning how we want to navigate the familiarity of our home communities. Over the past several weeks, we have sought opportunities to express our gratitude to one another for the unforgettable semester, and offer support and ideas for how to dive back into our lives at home. We have been considering our passions from this semester and how to carry them forward into our home communities. A collective stressor about returning home involves staying connected to the new aspects of identity that many have gained throughout our journey as students wonder what it will look like to transition back into home high schools. Common hopes about returning home include addressing new insights with friends and family, and learning how to incorporate the ways we’ve changed into our normal routines. After gaining comfort in our ever-changing daily routines, hitting the road for a new location every few days, and sharing all our highlights and the lowlights within our own group, a common discussion point is how to do justice to the stories we look forward to sharing. We’ve practiced elevator speeches about our experiences, discussed our aspirations and potential challenges in mentor/mentee pairs, and wrote warm and fuzzies to each member of our community. As teachers, we know the group will ultimately find a multitude of ways to further incorporate the lessons from our semester into their futures.

On our last afternoon, we celebrated with a fun and thoughtful graduation ceremony, complete with some classic final skits, and warm and eloquent words from everyone.

Our graduating seniors

Graduation for TTS30

Graduating senior caps

Our craftiest media genius Savannah made this awesome slideshow for graduation.

Learning at African Leadership Academy

Life moves quickly at The Traveling School. One moment we’re living full time in tents and with a large blue truck which houses our sole belongings for these months, and the next we’re stepping onto the manicured campus of the African Leadership Academy (ALA), preparing to form new connections and bonds with students and faculty from all over the world. ALA is a two-year secondary school which accepts top students from all over the world, with a concentration on the African continent with the hopes of inspiring and supporting a new generation of leaders and change-makers on the African continent. Founded 10-years ago, ALA has become a household name amongst prestigious schools and focuses on entrepreneurial leadership as well as African Studies. Through a budding partnership between The Traveling School and African Leadership Academy, TTS has the opportunity to visit ALA and both share our experiences as students and teachers as well as learn from ALA about the innovative learning environment. It is also a unique time for TTS students to live in dorms with “chommies” or buddies, and connect with students their own age.

Each day at ALA was jam-packed with activities and classes. Beginning with a 7 am breakfast in ALA’s dining hall, students slowly poured from dorms for food before morning classes. TTS students joined their chommies in classes ranging from Chemistry and Biology to “Omang,” an interdisciplinary class which combines African Studies, Entrepreneurial Leadership, and Writing and Rhetoric. Students were able to participate in class, offering their own thoughts on similar themes such as identity and social change. With TTS classes mixed in throughout the day, our days flew by quickly, ending each night with a BUILD workshop.

The BUILD program focuses on the practical application of entrepreneurship and enacting positive change in the world. The acronym, “Believe, Understand, Innovate, Learn, Deliver” serves as a model for ALA students during and after their time at the academy to lead more effectively. TTS students used these workshop to practice different teamwork strategies, leadership exercises and formalize ideas for their upcoming Zenith Project. The Zenith Project is a longstanding TTS tradition in which students identify a problem, issue, or topic they are interested in. The goal is to organize and cooperate to address the chosen project head on in an effort to become active and engaged citizens. Projects have ranged from gear drives, raising scholarship money to fund a community’s water system. Each project is fully headed by the students and depends solely on their commitment and drive after the semester. Using the “BUILD” model students brainstormed three projects which they felt passionate about and presented to a panel of ALA teachers on how they planned to enact positive change regarding three separate topics: funding a safe house in the Democratic Resettlement Community of Swakopmund, Namibia; funding foster care in the Knysna Township or focusing on education surrounding gender identity and LGBTQI+ rights in both South Africa and the United States. Students will continue to discuss these options as they collectively agree upon a project for TTS30 to undertake.

To explore off-campus a bit, TTS30 ventured to The Apartheid Museum and Soweto. Beautifully constructed and brilliantly curated, The Apartheid Museum provides a powerful and challenging visual experience that contextualizes the lead up to apartheid, powerful activists and politicians and pivotal moments. It would be easy to spend an entire day wandering each section slowly, though after even a few hours one feels emotionally exhausted. From the solitary confinement cells, to the police capture and videos of both the outbreak of violence in the 1980s and the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission, students and teachers grappled once more with not only the dark reality of apartheid but the recent nature of its history.

Before embarking on a long walking tour of Soweto (South Western Township), we refueled with a delicious lunch at Lebo’s, a flourishing hostel and guiding company within the township. Soweto is infamous in South Africa as a political hotbed which led uprisings and protests during apartheid and remains a politically and culturally dynamic space. Joining local guide Zigi, who was born and raised in Soweto during apartheid’s final years, we learned more about modern-day Soweto, how the community has changed and continues to tackle challenges and pursue equality in a post-apartheid South Africa. It is an incredible juxtaposition to have seen flames rising from the violence of the 80s and 90s in The Apartheid Museum, to stroll through calm neighborhoods, with children in the streets, walking home from school.

The positive and prideful outlook Zigi held for her community matched well with the vision and mission that ALA holds: there are strong, engaged youth who will advocate for their communities in order to achieve positive, lasting change. We hope that as TTS30 turns its eyes toward home and boards a plane home in just a week’s time that there is a balance in understanding both the deeply rooted challenges and inequalities faced today as well as the inspiring people and movements which have sought and continue to seek a better tomorrow.

Dear friends, family, and loved ones across the world,

Amidst the craziness of semester life, we wanted to take a moment to give thanks and allow ourselves to reflect on the gratitude we, as a community and as individuals, have felt throughout the semester. Though it’s tough to be apart from you all today, we are thinking of you and hope that, despite being several thousand miles away, you feel the extent of our thankfulness —

I’m thankful for my parents for raising me in a beautiful place I am glad to call home and all the opportunity they have given me and the hard work they have put in to get me where I am going. I’m thankful for my two sisters; Anna and Olivia, my grandmother, my “uncles”; Buddy, Brogan, and Tyler. I am thankful for my friends in Livingston, MT at the Shane Center. I am grateful for the lessons I have learned on this amazing adventure, the people I have met here, my newfound passion of science and the natural world, and everything in between. — Kate, 15, MT

I’m thankful for all of my family and friends who continue to love and support me despite how difficult it may be. Thank you for putting up with me thus far, props to you 😉 — Reeves, 15, GA

I am thankful for all the people who made it possible for me to be here. — Ra’Gene, 18, LA

I am thankful for the family that put the need for adventure in me and the opportunities I have that allow me to pursue it. — Sarada, 15, MT

I am thankful for my mom and Grandparents for loving me and making me who I am today. Thank you for always believing in me, and pushing me to be my best self always. Thank you for giving me access to opportunities. Thank you Lizzy, Michael, and Davey for being my best friends; being your big sister is such an amazing joy and privilege. I am thankful for my teachers who are my role models and for my 12 new sisters. I am thankful for all the people I have met that have inspired me and all the places I will yet to go!! — Sophia, 17, MA

I am thankful for the spirit of adventure and being surrounded by so many inspiring individuals who embody it. I’m thankful for the privilege of my passport, and, most importantly, for the people I love who support me, relentlessly and unconditionally, in using it to chase my dreams. — Savannah, Teacher

I’m thankful for having opportunities such as this one to open my eyes, and my loving friends and family who give me love and support. — Dylan, 15, WY

I’m thankful for the opportunities I have had access to because of my mom and the people I meet on my adventures. — Mia, 15, WA

I’m thankful for my two parents who raised me to understand my place in the world, two brothers who’ve shown me how to stand on my own, and two dogs that love me a little less than my mom. — Abby, 16, IL

I’m thankful for all of the wonderful people I have in my life, the places I have seen, and the opportunities I’ve been given. I’m thankful for the vastness the world offers and for having an able body to carry me throughout my endeavors. — Ellis, 18, CA

It seems that every year I realize more and more aspects of my life to be thankful for; my family who has loved and supported me for all my life and through every hardship, my friends who inspire and push me to go further. I’m thankful for the opportunities I have received, the connections I’ve made, places I’ve seen, and everything I’ve learned up to now in my life. I’m thankful for the life I have, and grateful to be able to live it fully. — Millie, 17, ME

I am beyond thankful for my family and friends who have created and encouraged my love for adventure. They live in smiles and back me up in any pursuit for happiness. I am truly grateful for having them in my life and the opportunities they push me to take hold of. — Amelia, 15, FL

I am incredibly thankful for my amazing and supportive parents who have encouraged me to follow all my dreams and help me pursue them. Mom and Dad, I love you to infinity and beyond and thank you for allowing me the opportunities to see the world and learn from all it has to offer. My brother Jack, thank you for always having my back and embarking on countless adventures with me. I am so thankful for this life-changing experience that has opened my mind and heart to the world I live in and my place within it. I am thankful for the TTS30 teachers who have helped me renew my passion for learning and education and have pushed me to grapple with the hard questions in life. I am thankful for all of my family, friends and supporters who have helped propel me into The Traveling School. — Hannah, 17, MT

I’m thankful for my family and the people who time and time again stand by me and support my dreams and fuel my ambitions. I love you mom, siblings, Crystal, Val, kids, Destiny, and everyone who has been there for me <3. — Shay, 18, MT

I am grateful for my family and friends who ground me regardless of where I am in the world. I am grateful to have a job in which my days are spent outside and finish with a full heart and mind. And finally, for the privilege of teaching and spending time with brave, curious, young women who challenge me each day. — Abigail, Teacher

From all of us, Happy Thanksgiving, we love you, and we cannot thank you enough for being a part of this incredible journey.

[ngg_images source=”galleries” container_ids=”30″ display_type=”photocrati-nextgen_basic_slideshow” gallery_width=”600″ gallery_height=”400″ cycle_effect=”fade” cycle_interval=”5″ show_thumbnail_link=”0″ thumbnail_link_text=”[Show thumbnails]” order_by=”sortorder” order_direction=”ASC” returns=”included” maximum_entity_count=”500″]

Garden Route Shenanigans

The Garden Route is one of South Africa’s most popular destinations, for both locals and foreigners alike. Even with its wild weather, it’s hard not to be enchanted by the winding roads, the smell of soil after a fresh rain, rugged coves, wetlands filled with birds and small harbors. It was the perfect change of pace after a long stay in Cape Town.

Our Garden Route adventure began in Swellendam, one of the oldest white settlements in South Africa. Sandwiched in between nature reserves and beautiful mountains, we re-started camp life. Happily setting up our tents again and re-united with Soko and Samukange, Amelia plotted a November 5th Halloween to make up for our lack of celebration in Cape Town. Despite low expectations of our access to costumes everyone turned out in full force. Shay, our resident make-up master, gave everyone’s look a boost, including using jam and ketchup to create blood and guts on Ra’Gene’s face. As Harry Potter is constantly read and spoken about, Kate, Dylan, Reeves, Millie, and Abby played everyone’s favorite wizards and witches. Perhaps the real winner (though we all received awards for costumes) was Ellis, who, without having to purchase a single item, arrived as Soko’s spot-on doppleganger. To continue the spirit, we hosted trick-or-treating at a few tents and the truck. Each stop demanded a different task: dressed as Audrey Hepburn, Abigail required students to sing or rap a song —preferably with a Halloween theme — to receive candy; the ghostly teacher Ali posed riddles; and Savannah, who happened to be dressed as a semi-colon, demanded a sentence employing a semi-colon correctly to avoid suffering jumping jack punishment.

Changing out of costumes, we continued on to the coastal town of Knysna. With a bit of time to catch up on classes, we shook out our soggy clothes and tents after an unexpected rain storm in Swellendam and soaked up the sun. With access to a volleyball court and trampoline at our campsite, PE classes received a boost in excitement as people leapt and a new passion for “nuke ‘em” – was born. During a visit to the Kynsna Township with a local tour company, students received a glimpse into the life of locals through focusing on the informal economy and entrepreneurship, students learned further about the continued contrast of intertwined communities.

Without giving Big Blue too much down time, we moved along toward Plettenburg Bay. Known for it’s beaches, we camped along Keurbooms Lagoon and fell asleep listening to the Indian Ocean’s waves and the wind passing through Eucalyptus trees. Seeking voices of people positively impacting communities and knowledgeable about place specific challenges, students visited PlettAid, a local wellness program and clinic to expand their current science unit on infectious diseases. Tackling issues ranging from increased health screenings, to educational outreach and HIV/AIDS prevention, students met the Wellness Program director and his team to discuss tactics for disease prevention, and learn about their education program.

Before long it was all hands on deck to prepare for our hut trip. Each mentor group planned meals, and our representatives Hannah, Ra’Gene, Millie and Ellis led the grocery shopping charge, with the heavy task of making sure we were well fed for our four day hut trip through the Tsitsikamma National Forest. After our never ending duffle shuffle, GORP mixing and a quick wave goodbye to Big Blue we began our first day hiking at Nature’s Valley, hiking from the beach into the lush mountains. Each day we hiked in small pods in order to allow for a sense of freedom on the trail, an ability to hold conversations and play games as a small group – a rarity at TTS. Our first evening was spent at the stunning Keurbos hut. With our food and duffles luxuriously dropped off, our weary feet were glad to pause for the night as we cooked a large meal of gourmet baked potatoes, brussel sprouts and mixed veggies over open fires. Tucked into cozy bunk beds, we awoke to another sunny day.

Never a dull moment in the Tsitsikamma, we passed over streams, across rivers, through pine forests, balked at the lush fynbos and danced through humid riparian environments. Singing voices carried us up steep climbs and rocky descents. Those who didn’t partake in late afternoon naps formed our motley cook crews, as Kate and Mia stoked fires, and Hannah chopped vegetables, we enjoyed a burrito night and quesadilla night. On our final night, listening to a fierce rainstorm roll over us, we cozied up in a bunk room to talk about what going home might look like. It is hard to balance staying present and preparing for the transition home. Students and teachers alike shared their experience so far on the semester, what their hopes and fears for transition are, and how they hope to hold onto all they have learned about themselves and the world. This is no small task, and we hope to continue speaking about it as a community as we all prepare for our return.

Luckily for us — we know some stateside might be a little more eager… — we had a few days of adventure left on the Garden Route. From our cozy huts and long hikes, we took a surfing break in Jeffrey’s Bay, and landed ourselves for a few final nights in the beautiful nature reserve outside of Port Elizabeth. Although a larger city, we would never know as we tucked in overlooking the Indian Ocean for our final nights in tents of the semester. To honor the wonderful, patient and generous Soko and Samukange, the group planned and cooked a feast for the final night with the truck, and our honorary dads for the semester. With the library and all our group gear packed away, we held an appreciation circle to tell stories about our wonderful months with Big Blue and the guys. We shared gratitude and passed along letters for Soko and Samukange’s families, so that they might know what having them as a part of the TTS community means to us.

With bittersweet excitement for the next phase of our groups’ journey, we hugged our token gents one final time, waved goodbye to Big Blue with misty eyes, and boarded a flight headed for Johannesburg. It’s hard to believe, as we dive into a beautiful partnership with The African Leadership Academy for a few days, that our days as TTS30 are coming to a close, and yet, we all know that this is merely the beginning.

Global Studies

In Global Studies, the students crafted interview questions, and conducted oral history interviews with their host families in Cape Town. The project sought to allow students to take advantage of the opportunity to learn more about their family’s experiences and perspectives. The girls focused their questions on South African history, or post-apartheid politics, and learned a huge spectrum of fascinating stories. Excerpts from Sarada’s description of her interview, and reflection on the process is below. She begins by describing the racial classification system, and how it affected host family. Under the Population Registration Act of 1950, individuals were racially classified as black, white, colored, or Indian. This had devastating consequences, based on specific areas where different populations could reside and work.

Oral history report and reflection

By: Sarada, 15, MT

…One way new apartheid laws began to affect coloureds was by splitting up families. Apartheid authorities would ‘test’ coloured individuals to determine their if they were to be labeled as coloured or white. They would put a pen in every family member’s hair, and if it fell out they were white. This system was teaming with issues, but one was that two siblings could be labeled as different races. Stafford explained that if one family member was labeled white, they would not longer contact the rest of the family, because they became an embarrassment. This split happened in Stafford’s family. His mother’s oldest sister was labeled white, and immediately distanced herself. She moved away and no one in his family heard from her until her mothers death. She then wrote to say she could not attend the funeral, and asked to be sent a ring her mother always wore. She was sent the ring, and responded by saying thank you, and to please not contact that address again…

…Our next question was the one I was most curious to hear the answer to. We asked if during apartheid Stafford had hope for its end. He immediately shook his head. This was the question he had the greatest difficulty forming thoughts on. He kept shaking his head, saying phrases such as, ‘never in our wildest dreams,’ ‘not in our lifetime’, and ‘not without a civil war.’ Every other person I have spoken to about this says things like they never gave up hope, or somewhere inside they knew. Stafford’s answer felt more real. I could see the conviction in Stafford as he struggled to find words, something he had never done before. His answer was beautiful in how genuine it was. This also made it sad, because it demonstrated how hopeless apartheid could make individuals.

Stafford Jacobs is a caring and passionate individual. He was a leader in the first bus boycott, he watched the moment Nelson Mandela walked out of prison, he played a first hand role in resisting apartheid. He was able to give us a first hand account of actions here in South Africa, always emphasizing the injustice, and the degree that everyone needed change. When asked what he wanted people to understand about apartheid, he said, ‘the extent to which it dehumanized people solely because of the color of their skin. They are more than that.’

My interview made me view apartheid more realistically, and see first hand its individual effects. Since we started studying apartheid, I understood how inhuman it was, how ruthless some of is advocates were, but in my mind I still had the idea of the oppressed staying determined and never losing hope. Stafford exemplified that apartheid brought a hopelessness, but despite losing hope about seeing the end of apartheid in his lifetime, he did not let it consume him. He continued to go to work, raise children, and have hobbies. The lack of hope for the end of apartheid did not make him any less strong. I think it some ways it actually made him stronger, he still chose to fight something he did not think could be beaten, because he understood that hopeless did not mean helpless.

I also learned about a side of apartheid that I had not before. Stafford did not live in a township surrounded by crime, and he was not a rich, white oppressor. He was neither extreme, but he still told me about his church service getting tear gassed, his students getting arrested, and his white neighbor refusing to acknowledge his presence. Apartheid was a system that oppressed all non-whites, based on undermining the people ‘below’ you. Stafford made apartheid seem less distant to me. I could find a lot of similarities between how Wendy and Stafford live, and how I live. This made it easy for me to put myself in their shoes. Stafford allowed me to see and understand apartheid more completely, without the lens of hope that my life as an upper middle class white person provided me.

Literature

Literature class recently crafted drabble projects, which is a brief work of fiction. The aim of the assignment is to include all the aspects of a longer work of fiction, but eloquently express meaningful ideas with brevity.

Drabble

The Dying Art

By: Kate

I live on a gusty rolling lump of clover and moss. Inside my home, scattered, are crowded letters whisking me from what I know. Sliding me into the uncomfortable, washing me in endless memory. Memory that resonates long after the print date. I’m built for these news clippings, short but poetic reminders. Then, I wonder why out of a thousand blooming stories, these are plucked, but then, I hope. That I may be a blossom picked, a story worth telling. I have the oh so common human need to be admired and to be loved. To have a story told.

Drabble

By: Shay

My hair grays.

“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” that’s what my mama always told me.

Dear Diary,

Forty seven years ago I went to the San Living History Museum. I was in awe, women who were strong with babies on their backs, singing and dancing.

“You see that Jane?” My mother questioned me, “their skin looks like ours.”

“Beautiful” was the only word I could utter. Seeing the way the sun aged their faces but they could still smile, I was mesmerized. I never knew my people could be so confident, so beautiful. I was forever changed.

Cape Town Living

Robben Island Nelson Mandela’s Cell

Hurtling south in Big Blue, with only one brief night in the Northern Cape, we arrived in Cape Town to begin a new form of exploration: city life. With Table Mountain looming 3500ft over the city center, the condensed energy is immediately palatable. Upon

our arrival, our Chieflet, Reeves, sprung to action to have everyone off the truck and settled in our new home in the Gardens neighborhood. It is easy for TTS to take over spaces and it is n

ever more clear than when we descend upon a h

ostel. Luckily our longtime hosts appreciate our energy as white boards, butcher paper and calculators begin to appear at regular intervals.

Without a moment to spare, we spent our first full day in Cape Town visiting the townships of Langa and Gugulethu. As the oldest township near Cape Town, Langa holds particular historical significance and has capitalized on the interest of tourists in the systems of apartheid which remain present today. Innovative and inspiring, the Langa Cultural Center boasts a pottery studio which employs locals, music rooms, a crafts market, a café, and a theater. With our local Cape Town guru, professor Toni Sylvester, — with whom The Traveling School has been working for 13 years — we learned about the process of revitalizing a neighborhood from within. In Gugulethu we learned about an after-school program which employs community members and works to promote education through directed tutoring and increasing admission to prestigious high schools and subsequently university. Ra’Gene, a senior, peppered our hosts with questions about the process of graduating and seeking higher degrees as we discussed the educational system of modern day South Africa.

It is impossible to understand Cape Town without seeing the stark contrast of a township such as Gugulethu, which was assigned to blacks during apartheid, and the nearby white suburbs. Continuing on our tour we passed through lush, green neighborhoods which host primary residences and second homes alike. Woven into gardens along the base of Table Mountain, grand homes and properties sit within 15 minutes driving distance of the Cape Flats. It is a dichotomy which fascinates, captivates, disturbs and confuses many who are unfamiliar with the history or modern reality of South Africa. Students had no shortage of questions for Toni, our local homestay coordinator, as we began to use Cape Town as a microcosm of the entirety of South Africa.

To add context and depth to Cape Town, we cannot simply skim the surface with a township tour. To deepen our conversations, we visited The University of Western Cape where Toni teaches, and attended a class on gender identity and politics given by a trans student who is receiving a Masters in teaching. Able to walk the campus, everyone was in the college spirit as the bustling student center filled with various political groups, student associations, athletic teams and residential students.

Launching ourselves from the modern academic context into the steeped history of activism during apartheid, students and teachers boarded the ferry to Robben Island to learn about the stay of not only the late Nelson Mandela but thousands of other political prisoners who were kept on the infamous round of land in Table Bay. Led by a former political prisoner, students learned about the history of the island as leprosy colony, until its modern day, as it seeks to honor the sacrifices made in the name of human rights and the “triumph of the human spirit” in the face of injustice.

Returning to their homestay families each evening for home cooked meals, students regathered the following day for an outing to a primary school. Split amongst classrooms to help teachers, TTS students read, played games and shared stories with students ranging from 6 to 13-years-old. As a non-fee paying school, students come from underprivileged backgrounds in local townships. The school provides food for approximately 600 students each day, and attempts to provide a safe haven amongst the prevalent gang violence of the neighborhood. Students in the older classes asked Shay and Hannah about the United States: is there violence there? What does your house look like? And just as we seek to breakdown stereotypes of the places we visit, so too do we seek to provide a larger understanding of The United States as we visit communities. As TTS students stepped out of the classrooms after a few short hours, new acquaintances waved and laughed at the students with funny, American accents. Dylan and Kate remained surrounded by their new companions, holding their hands and legs, they wiggled and laughed, hoping for more time. Ellis snapped photographs of a mural encouraging schools to be “safe spaces” for all. TTS students are challenged to process so rapidly that there is perhaps no better grounding visual than standing with students in a schoolyard to contextualize what South Africa is still fighting for: equality.

We followed our school visit up with a conversation with lawyer Kelly Stone — an old friend of Abigail’s — who works as a law consultant on the Civilian Committee for Police and Security Oversight. American but married to a South African, Kelly provided a unique perspective on the transition from a security state to a democracy and the daily work that South Africa must still put in to achieve its goals and honor its constitution. From Sophia’s enquiry about the role of police in managing domestic violence, Abby’s curiosity surrounding university protests and the use of private security, and Mia’s question regarding hope for the future of South Africa, students posed challenging questions and impressed Kelly with their depth of knowledge and commitment to understanding.

We filled our final days with science and literature classes alongside a picnic at the stunning Kirstenbosch Botanical Gardens, wandering through Green Market Square, and tasting the delicious, worldly cuisine that Cape Town has to offer. For a final evening of exploring the vibrant culture of our temporary home, mentor groups dashed between art galleries on “First Thursday” in which galleries stay open for evening viewings throughout the bustling city center.

It would be possible to spend an entire semester studying the intricacies of South Africa and use Cape Town as a base for understanding the beauty and complicated reality of the young nation. Sarada and Amelia even debated how they might return again, in a different phase of life, to explore further all that this wonderful city has to offer. Alas, waving goodbye to Cape Town and heading east on the Garden Route our Cape Town explorations will continue to guide our conversations and remain a memory of awkward first hellos with host families, to adventures with host siblings on the coast, and visions of a society in progress.

Academics in Action

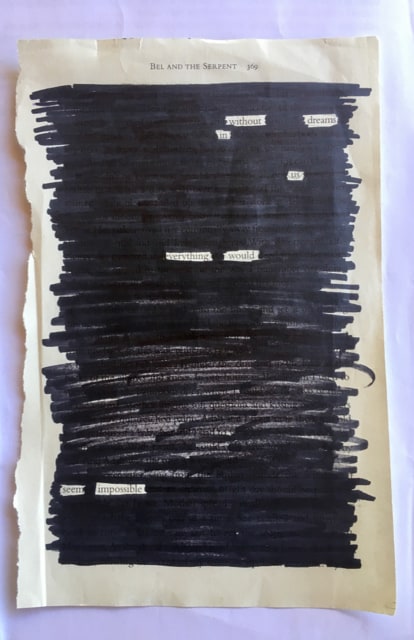

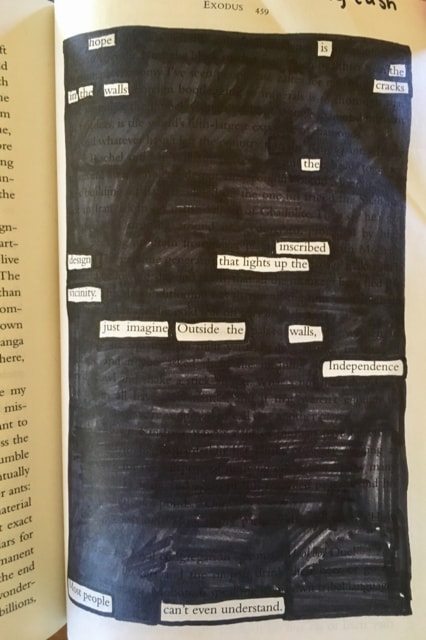

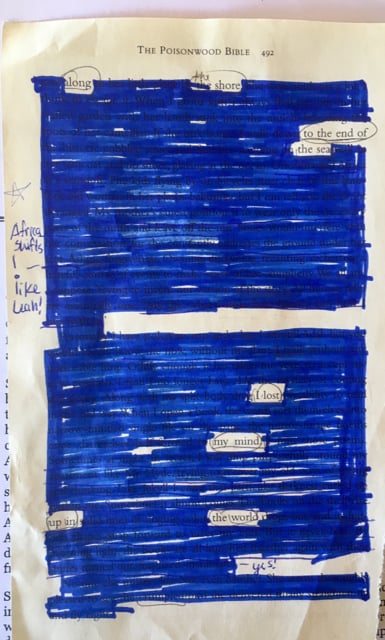

Blackout Poems in Literature Class

Words are magical! Students recently played with the power of phrases to create poetry from a passage of The Poisonwood Bible. Although intimidating to black out lines of a book, each student surprised herself with the power of a few words dispersed throughout a page. Go ahead, try your own blackout poetry.

Millie, Senior, Maine

Shay, Senior, Montana

Amelia, Sophomore, Florida

Geology in Science

In science class students have been exploring the landscapes of Southern Africa and the geological forces that have shape

d them. At the Fish River Canyon, we created a visual timeline of the earth’s history and were able to identify major events that corresponded with each visible layer on the canyon walls. Next, students created analogies to illustrate the different layers of the earth, and experienced the rock cycle from the perspective of a single rock particle. The students are using the knowledge they’ve gained about geological processes to research the history of a handful of the places we’ve visited throughout the semester.

More photos on the shared drive HERE.

Including the last couple of weeks & the campus visit!!!!

Academic Update

Science Class

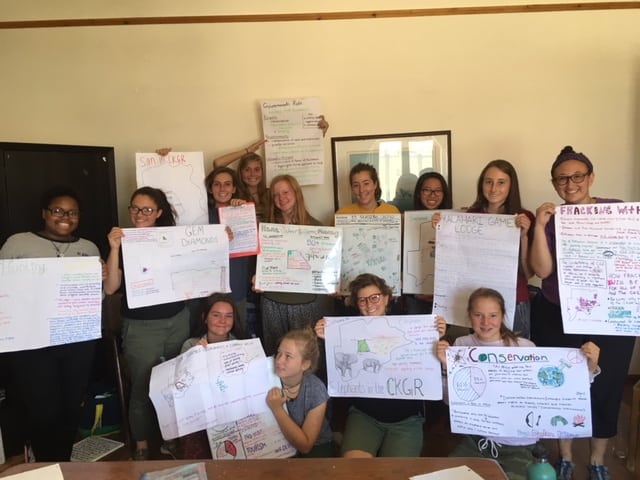

In the science town hall meeting, the girls represented various stakeholders, each with a different priority and perspective about how to use the land in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. Their was a huge spectrum of interests and concerns. The conservation perspective worried about access points for elephants, seeking to minimize human wildlife conflict. The frackers were adamant about the necessity of their solution to aid in Botswana’s growing energy demands. The diamond, silver, and copper mining contingent argued for maximizing the untapped resource potential that lies deep underneath the CKGR. The role of tourism was emphasized by lodge owners and a minister of environment. After hearing out thirteen different proposals, the girls had the challenge of creating a final solution, that the contingency would all agree to. Ultimately, their comprise designated different parts of the CKGR for a variety of uses. There were some mining concessions that allowed for returning ancestral lands to the

San people, and they were allowed to return to subsistence hunting. Tourism could continue in conjunction with incorporating the San people’s perspective, and presentations of their culture as an example of how to live harmoniously on the land. The class’s thorough and convincing presentations, and patience in forming a complex and creative solution made for a lively but respectful collaboration between the representatives.

Travel Journalism

Students are often asked to explode and reflect on a moment throughout our travels. Recently, Travel Journalism ladies were asked to make our visit to the Democratic Resettlement Community (DRC) pop out through descriptive writing. Below the students share their work, trying to bring you into this settlement on the other side of the wall outside Swakopmund, Namibia.

Hannah, Senior, Montana

During our week spent in Swakopmund, we coincidentally met a woman by the name of Katrina. She is the first black shop owner in the town of Swakopmund, and she had just opened her coffee shop. We visited her shop, and learned more about her and her work. In all that Katrina does, her mission is to help those in need. She truly wants everyone to get the most out of life and intends to help in every way she can. Katrina has and continues to help kids get out of tough situations involving drugs, alcohol, and lack of parental figures. She brings kids into her home and offers them safety and work, encouraging them that there are other options in life. She employs many of her sons and daughters that she has taken in at her coffee shop. In the Democratic Resettlement Community, Katrina established an after school program out of her own home, where children of all ages come to participate in arts and crafts, games, and singing and dancing. A meal is offered once a week at the end of the arts and crafts session. She brought us into the DRC to witness first hand how her program runs. Children running around holding an assortment of colored pencils, were singing and dancing, as we stepped off of Big Blue to join them. Interaction with the children is effortless, as they are so full of joy and love, playing with each other and visitors. Katrina’s home offers love and kindness to children seeking it, and the program is also run by her friends and relatives. Katrina’s compassion and drive to help people is evident upon her interactions with all children, her own children, biological and not, and when she shared her work with us.

Millie, Senior, Maine

Our big blue truck winds its way carefully through a sea of low, tin houses. From my vantage point through the back window, I can easily see above the roof tops and into the distance, where small home after small home disappears into the ripping winds that sweep through the Democratic Resettlement Community, bringing sand from the Namib Desert into the dirt streets and open windows. Nothing stands out in this vast city of tin buildings. There are no brightly colored billboards or water towers, no telephone poles or playgrounds, just a maze of brown houses, slowly succumbing to the sand and ocean storms. 20,000 men, women and children live here, but for all the people, I see so many dirt streets, filled with swirling sand, and residents jogging from home to home, heads bowed low against the incessant winds. The DRC, where Katrina and the majority of black people in Swakopmund live, has no electricity, running water, school or grocery store. Children walk miles to go to school, needing to enter the city portion of Swakopmund to get an education. On their long journey, they will pass to the other side of a wall, which separates the DRC from the ‘center’ of Swakop, containing and hiding the poverty and people from the eyes of the wealthy residents and foreign tourists.

Ra’Gene, Senior, Louisiana

One person I connected with at the DRC was Katrina’s daughter, Antonetta. We first met her at Katrina’s coffee shop, where we were also introduced to Katrina’s three other children. Katrina and her daughter then rode with us to the DRC so we could get a broader understanding of the work Katrina does. When we arrived at the after school program at Katrina’s house, TTS30 girls began playing games with the kids. During one of these activities, Antonetta and I began talking. We talked about everything from high school classes to applying to college. We also talked about friends and the struggles associated with school and everyday life in the DRC and in New Orleans.

This encounter was the first time this semester that we got to befriend someone within our age group. Watching Antonetta care for children at the after school program, and hearing her passion for studying aviation showed her drive to rise above what her community provides. Although she continues to go to high school and is planning on going to college, not everyone in the DRC has this opportunity. She explained to me that once kids grow up and head to high school, they frequently start dropping out and are ‘lost to drugs and alcohol.’ Katrina’s daughter has a unique support network that has given her an advantage and an opportunity to consider a different type of future than many in the DRC are afforded.

Ellis, Senior, California

During our time in the DRC, we danced, sang, drew, made crafts, and played games with the children at Katrina’s after school program. A group of middle school boys taught me magic tricks; their eyes focused eagerly on mine, waiting to see if I could figure out their trick. In return, Reeves and I made a cootie catcher with all of our names in it. We took turns choosing a color to stop on and spell out, which led us to the fold of paper with one of our names lingering underneath the flap. We decided that name would be the winner, and they would get to keep the cootie catcher. I also spent time drawing various pictures with a little girl who did not say her name. We passed the paper back and forth between us until what was once a startling white piece of paper was now covered with houses, flowers, cats, hearts, and just about anything else we could conjure up in our heads. Once there was no room left for coloring, the girl reached up to me without saying a word. I walked around the room holding her, playfully bouncing her up and down. She buried her head into my neck, and I could tell she wanted affection. I rubbed my hand on her back, and tried to be as warm and comforting as I could.

History class trip to Shark Island where the Marine Denkmal monument lives. One of the very few warm and sunny days that ever exist out there.

History Class

History class visited the Marine Denkmal monument in Swakopmund, and read this recent article during our visit. The article is from the New York times and describes the controversy surrounding the memorial: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/21/world/africa/namibia-germany-colonial.html

The monument commemorates the German occupiers that brutally crushed an uprising by the indigenous Herero and Nama groups. The class learned about the concept of historical memory, and how communities and groups subscribe to a particular narrative about historical events. The students were astonished by the implications of a memorial in the center of town, which remembers the encounter that resulted in the massacre of 65,000 members of the Herero and Nama tribes. The students reflected on their connections about the implied historical memory of the community of Swakopmund, and how the United States often chooses certain historical narratives to embrace, and other stories that are more convenient to overlook.

Reflection on historical memory

By: Ellis, Senior, California

The fact that the statue of Marine Denkmal is still standing in the middle of Swakopmund demonstrates how immense of an impact the Germans had on the town. It represents the taking of the land by settlers in an extremely disturbing manner, and it baffles me that it is accepted by so many citizens. The (not complete) lack of outrage just shows how easily people forget the past, and that outside influences are more than capable of clouding the public’s perspective of the past. It seems that over time, horrendous events are passively accepted, purely because there is distance between when the situation occurred and the present.

America appears to remember historical events in whatever way makes us look and feel best. One example of the US that depicts our historical memory is Thanksgiving. The majority of US citizens celebrate that day with a massive feast, where they go around and express what they’re thankful for. Schools allow students to dress up as ‘Indians and Pilgrims’ and play games. We do not want to acknowledge the fact that we are really celebrating a time when Europeans invaded and mass murdered Native Americans. The way that the US chooses to remember things highlights our desire to be seen only as a nation that has reasons to triumph, and no reason to be ashamed. We want to remember events in ways that hide our dirty deeds so that our guilt can go without being noticed. History has not been a straight line to success and happiness, and it’s dangerous to look at it that way. Our school systems and textbooks continue to preach of stories that significantly alter the truth. If we teach our children that the past has been nothing but smooth sailing, and that our victories were made without blood, they will have an unrealistic perspective of our history. This allows kids to grow up believing false stories, and that is not fair to them or the people who suffered in the making of or country. It is not acceptable to keep people in the dark when it comes to the roots from which their entire life has been built.

By: Millie, Senior, Maine

The presence of the monument without the red paint teaches us that the German community still remember the fights between the Herero / Nama and themselves, and that they are proud of how bravely the fought (judging by the stance of the man who would not leave his dying comrade). However, the red paint adds a new perspective on the monument. The paint was splattered, but not below the dying man to symbolize blood, but beneath the feet of the strong, standing one. This teaches us that there is more conflict to the monument than we see, and also more to history than we know on first sight.

One specific way the US remembers and views the past is on Thanksgiving. What the story began as is much darker; Europeans came to the New world, killed the Native Americans, took their resources, and ate their food. Now on Thanksgiving we give things to our friends and family, not even thinking of those who gave their lives so that we could thrive. We remember it this way because we don’t think the Native Americans are worth remembering; if white Europeans had gone through the same thing, Thanksgiving would be a day of mourning. We remember what we think is important, and therefore Native Americans were not important. Another way we remember our history is in monuments or art forms. Take Mount Rushmore for instance; people who were important to US history were carved into solid rock for us always to see. It makes a statement, and tells the nation and world that these white men were important to our history.

The consequences of historical memory to our country is that we look inconsiderate for our actions. Some steps we take may be positive, like the Holocaust memorial in DC to show our sympathies for such a tragedy. We have to be careful what we remember in our history; as a majority, the US is a privileged nation, and we need to remember that we are privileged enough to be able to choose what we remember. We must think of the facts in our history, and of both sides of the story.

Mock Trial

History class has also been working on creating a mock trial, focusing on a case study of the colonial occupiers and independence movement in Namibia. The class learned about the first genocide of the 20th century, which occurred at the hands of the German military. German farmers were attacked by indigenous groups that were unjustly treated during colonial occupation, which began a war that ended in tragedy for the Herero people. The class also learned about the 100 year struggle of Namibia to gain independence, and were driven to extreme lengths in their desire to create their own nation. They were ruled by Germans, and subsequently South Africa, who implemented a brutal form of cheap forced labor, the contract labor system. In the case of South West Africa vs Foreign Occupancy, students played attorneys, witnesses, and the judge. The prosecution represented the people of South West Africa (present day Namibia). The prosecution fought tirelessly for justice, in the name of those whose dramatic history and suffering all too frequently in history goes unnoticed. The defense represented the foreign occupiers. The defense team impressively owned the colonial perspective, and fiercely argued that the colonial occupiers were doing a justice for the ‘natives’ in civilizing the wild content of Africa.

Here is some additional reading, in case you are interested in further background.

Below are the opening statements, written by the lead attorneys of each team. We wish you call could have been there to hear how convincing and realistic the event felt in real life. The defense team kindly requests that you understand that their case represents an embrace of the dehumanizing psychology of the foreign occupiers in their treatment of the local populations, and does not represent the actual views of the students. Both sides brought believable and impressive characterizations. In this trial, the defense was found guilty of the charges eloquently described below by the prosecution.

Opening Statement

Lead attorney for the prosecution

By: Abby, Junior, Illinois

Five men, powerful in stature, and far more powerful in will, traveled across five countries, 1000 kilometers, each carrying an old time assault rifle. Over mountains, through deserts, across borders armed by men prepared to shoot at the smallest provocation, they voyaged. And what brought them to do so, you may ask? It wasn’t a desire to kill or their savage instincts that drove them to this great act of perseverance, as the defense may tell you. It was pure desperation to live an unchained life, to watch their children flourish instead of struggle with every muscle in their bodies to survive, to finally end the perpetuating cycles of racism controlling their every move. These men marched with all their fight for a chance to truly live. They marched for independence from decades of European occupation. These men are not heroes. They are survivors.

Hello, your Honor, my name is Abby and I have the pleasure of serving as the Namibian government’s prosecution lawyer during this trial. Among my three witnesses and direct and cross examiners, I intend to prove to you today, without a doubt, the foreign occupiers fault in wrongful governance of the Namibian people. Our charge? Workplace malpractice, wrongful dispossession of land, blatant disregard for human rights, and genocide.

A rather intimidating list, I am aware, but the horrific acts of the German government and South African occupation call for nothing less. Those foreign occupiers are not fundamentally evil, as the Defense may claim the Namibian people to be. They are not psychopaths, they are, however, power hungry men, caught up in authority and wealth. They are murderers, don’t let the Defense convince you of anything less.

This trial is simple when you take a step back. We are amidst a trial about race. The very foundation of this continent’s nations were sketched without the input of those actually affected. Hierarchies were formed and enforced on the fundamental value that one race was superior. Black, Namibian children grew up learning the were less human than their white counter-parts. And this mindset cannot simply disappear with the taste of independence, it has been embedded deep within Namibia’s core. Awareness and recognition of these systems, and all the symptoms they’ve created is the next step to a free Namibia. Don’t allow those five brave men to have marched for nothing. The defense’s first witness, Lothar von Trotha, is a racist, power-hungry serial killer with no value for human life left in him. Following, is a representative of the contract labor system, who will claim to be an employer of otherwise unemployed, impoverished men. Their savior. Don’t be fooled, she is nothing but a weak woman with inexcusable ignorance. Lastly, Frauline Amelia Elke will be unable to see past her own, limited experience. She is a naïve woman, unable to question things from multiple angles.

Today you will have the pleasure of meeting a representative of the Ovaherero, who narrowly escaped the genocide of her people, and suffered through 65,000 losses. Her testimony will uncover the necessity of this word: genocide, and all it stands for. Next you will hear from a representative of the Ovambo people, a hardworking man with a plethora of experiences and knowledge. He will enlighten us on the true life of a contract labor system employee, examining the animal-like treatment and unthinkable inequalities of the workers. Finally, you will be introduced to former president Sam Nujoma, an honest, selfless man, of which I am proud to know. He represents the independence movement, and will explain why these extreme acts were not precedented, but necessary for his people’s future.

Lead attorney for the defense

By: Sophia, Junior, Massachusetts

I know enough of these African tribes. They only yield violence.

Hello, your Honor and worthy opponents. I am von Lichenstien, lead attorney on today’s case, and I will be representing the German-Namibian’s in the fight against the violent Herero, and accusations against the brilliant contract labor system made by the Ovambo people and Sam Nujoma.

The overall case we are discussing is how the Herero peoples have unjustly attacked and treated German-Namibians, since the very beginning when the first German farmer stepped on this soil. As soon as we got there, all we wanted was to make peace and co-exist with the Herero. We loaned them a large sum of cattle and money to show them just how willing we were to work with them. We trusted the Herero with resources we were told would be reciprocated back. When the Herero people could not pay us back, they killed 126 of our men. The German-Namibians had no choice but to defend themselves through war. Lothar von Trotha, a general I am representing today warned the Herero people quite clearly on October 2, 1904: “The Herero nation must leave the country. If they do not leave, I will force them out with a cannon. Every Herero will be shot dead within German borders. If Herero people came into the German territory, as they were warned not to, they were placed in hostilities (translation: concentration camps). Your Honor, why are we, the German Namibians, being attacked today, when we followed through with our warnings. We German-Namibians acknowledge there were prisoners of war, we acknowledge we killed Herero people, but we were protecting ourselves. Every move the German-Namibians made was laid out to the Herero people. It is not the German-Namibians to blame when the Herero people willingly put themselves in danger, by coming to the land von Trotha warned them not to approach.

In the 1920’s through 1971, a contract-labor system was created during South Africa’s occupation of Namibia. Ovambo people were starving, poor, and in search of work. This labor system allowed Ovambo people to survive, and have a place to stay, and food to eat, and gave clothes to these workers. It does not make sense that these Ovambo workers would complain about working all day. Everyone works. The Ovambo people got paid, received food and had a place to live, the Ovambo workers would have died if not for these job opportunities.

The opposition, a violent Herero man, an ungrateful Ovambo, and a terrorist, the first president of Namibia, will be telling you complete lies. The Herero man will tell you that the German-Namibians stole their land. Your Honor, legally you cannot accuse us of taking land that was never legally the Hereros. The Herero will tell you that the ‘concentration camps’ were not comfortable. It was not comfortable for the German-Namibians to have to defend themselves from wild, uncivilized, ignorant savages that do not listen to simple orders by von Trotha to leave German territory. The ungrateful Ovambo will complain about the harsh weather and how hard it was to work. Guess what, your Honor, it was no the German-Namibian’s fault that the weather was unsatisfactory for a laborer. The Ovambo might mention how he was enslaved, which makes no sense. Slaves by definition do not get paid, which he was. And Sam Nujoma. His personal foundation states that after 12 innocent unarmed people were massacred, it was Sam that was arrested and charged for organizing this terrorism, out of anger about apartheid. Sam might mention how he hated German-Namibians. Who brought a government to Namibia, and proper education? German-Namibians. Who civilized the savage Herero? The German-Namibians. Even Sam himself was educated by a Finish and German school.

Your Honor, I will now proceed into telling you about the witnesses I am defending. Adrian Dietrich Lothar von Trotha, a German general, did not want to fight with the Herero people. He was considerate enough to warn the Hereros not to come into German territory. He did not start the conflict, the Herero did, by murdering 126 German-Namibian farmers. Leisel von Leich, the German-Namibian supervisor gives homes and steady work to Ovambo workers that would otherwise be dying of starvation. Leisel has included the Ovambo people into the cash economy. Frauline Amelia-Elke, whose ancestors came to Namibia looking for a place to call their own, were brutally killed by the Hereros. She feels that the Herero are still, after so many years, harshly aggressive towards other German-Namibian farmers. She is scared for her well-being and livelihood.

I want to review of the essential themes of our case.

- The intent of the German-Namibians was not at all genocidal, it was purely self defense.

- Legally, you should not rule that our self defense methods in the war against the Herero was genocidal, because the term genocide was not yet created or against the law at the time (the term was not created until 1948).

- The contract labor system was not slavery, the Ovambo were given a medical exam, a place to stay, food and clothing.

If you side with the opposition, you are ruling that every single wrong-doing or war a country participates in should have to be compensated for years passed the issue, and that notion is just not feasible.

Thank you, your Honor for listening to our case. We hope you can see our points, and rule in favor of the foreign occupiers. Let justice take its course.

Campus Visit 2017 – Namibia

An adventurous crew of parents, aunts, grandmas & family friends joined me in Namibia for eight days with the intrepid TTS30 group. We wish each of you all could’ve joined us, but hopefully we can give you a glimpse of our adventures through our words and photos. Here is the song the group sang to us upon our arrival: Welcome song video

I don’t know about the other folks who recently joined the TTS30 crew for the Campus Visit, but my brain has nearly caught up with my body after that crazy time travel back from southern Africa. The time with the group was jam-packed with educational activities, classes, presentations, wildlife viewing and so much more. Those TTS30 ladies are nonstop!

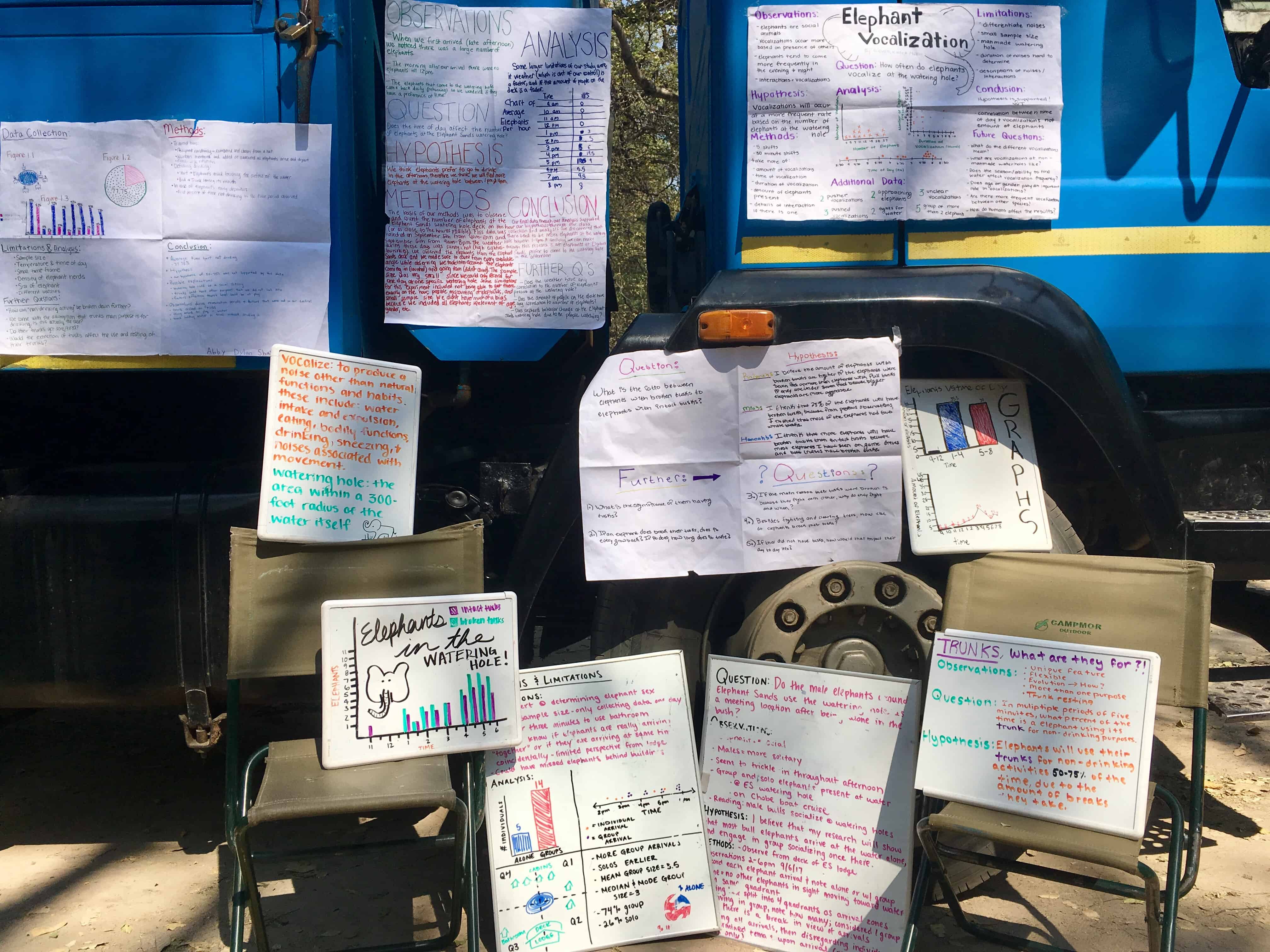

Our Campus Visit group converged in Windhoek, Namibia and eagerly met up with the students in Etosha National Park. Known for its massive salt pan, watering holes, and prolific wildlife, Etosha is home to four of the Big 5 (all but the Cape Buffalo) and many species endemic to the area. Since it hadn’t rained since February, the watering holes posed as backdrops for action movie sets with various species queuing for their turn to drink.

Students and parents packed into Big Blue and the parent’s safari jeep for early morning game drives and were rewarded with watering hole miracles: elephant family bath time; giraffe mother and child negotiating deep curtsies to sip water; elusive rhinos secret nightly rituals full of courtship and rivalry; a pride of lion spook stoic zebra unwittingly blocking the route to water. As cool mornings transition to sweltering afternoon temps, all animals search for cool water and shade – even our hearty TTSers enjoy poolside study time to beat the heat.

Next, we loaded up headed for the Cheetah Conservation Fund to soak up founder Laurie Marker’s efforts to save the wild cheetah. (Smithsonian article) Marker’s focus on noteworthy solutions to human-wildlife conflict with neighboring farmers have been successfully duplicated throughout the region. Touring her model farm, we meet herding dogs bred and subsequently sold to protect local farmers’ goats, sheep and cattle from predators like cheetah & leopards. Luckily, our tour included time for goat-wrangling and kraal cleanup as well as captive cheetah poop and bone collection. We learned about cheetah husbandry for the captive cheetah population on the property that would never be released to the wild; met with CCF’s geneticist; observed cheetah feedings and runs; and practiced predator identification using papier-mâché goats as models.

All the while, students engaged with our visiting family members and the people around us. They logged long days – with planned CCF activities from sunup to lunch, presentations for CCF staff and volunteers in the afternoon, followed by TTS classes, dinner and study hall. Did I mention that these girls are driven?! The TTS teachers orchestrated each day like a symphony – and set up enriching activities to bring out the most of each community we encountered. One such opportunity was a Global Studies class with guest speakers – Gerhard, our Namibian guide of German descent, and Ignatius (or Iggy), our CCF coordinator of Nama descent. Student and parent questions ignited powerful conversation and illuminated a few of the myriad perspectives regarding Namibian issues of land ownership, education, tribal conflict, and the history of German genocide on local peoples. It still gives me goosebumps to remember – especially when later, Gerhard told me he was caught off guard by Iggy’s responses – proving how important it is to engage in thoughtful conversations to understand each other’s point of view.

There was even a bit of downtime sprinkled in along the way – family and friends were invited for a traditional braai at the student’s campsite where Samakangay & Soko (our cook and driver) prepared the girls’ favorite meal – sadza (a Zimbabwean staple) with mixed grilled. Entertainment accompanied the meal – students hesitantly shared intimate “Where I’m From” poems, leaving no dry eyes in the audience. Each student picked a central line from her poem which Millie and I arranged to create a Community “Where I’m From” poem. See Savannah’s introduction to the “Where I’m From” Poems: Video

Where I’m From Community Poem

I come from the uncertainty of not knowing where I’m from.

I am from open and closed minds but always open doors.

I am from a family of wisdom seekers.

I am from the Crazy Mountains and Electric Peak where sky and stones continue to meet. I am from cold mornings that leave your breath hanging.

I am from finding sentiment in almost everything, never willing to let go.

I am from sandy floors whose beauty diminishes with the sun, revealing faded planks of oak stained with stories that come alive when no one is watching.

I am from learning to drive on big red tractors and VW vans that break down before we leave the driveway.

I am from my most authentic place: the middle seat, tucked safely between my brothers’ boney, empathetic shoulders.

I am from snowy windows and tropical storms.

“I love you to the stars and moons” from states away.

I am from roses for my Namma, peonies in mason jars. I am from Mama’s hanging flower baskets suspended in color, below the waving stars and stripes. I am from Daddy’s homegrown tomatoes growing homes for cocinells.

I am from hearts full of love, lungs full of laughter and 15 years of memories.

I come from growth within myself, adventure, and curiosity. From the challenging moments that help describe me, but the endless laughter that drive me.

Watch the video to see the students recite the “Where I’m from” community poem: Video

Our final dinner included entertainment where students showed off their dance moves; fine dining including Oryx steaks, cheesecake and Appletizers; speeches of thanks; and an awards ceremony that will go down in TTS history. Mary Beth and Gail reemerged as our hilarious hosts with notable acting credit and shout-outs going to Danika and Ali as well as a cameo appearance from Abby and Reeves. While it was difficult saying goodbye to the visiting friends and family, it was time for the band of travelers to continue along their route without us. I stuck around for a few more days to see the group settle back into to their semester rhythm, broadcasting their Willy Nelson theme song as Big Blue pulled away. Onto the next adventure!

We pulled into the Skeleton Beach Backpackers in the touristy beach town of Swakopmund, Namibia – Little Germany on the edge of the world’s oldest desert in Africa. Dylan and Reeves eyed the beach and surfers suiting up in wetsuits. The girls rolled out of the truck with perfunctory expertise and couldn’t disguise their anticipation awaiting their room assignments – rooms beds, fresh sheets and overhead lights – the first since week 1 in Zambia! They suspiciously eyed the afternoon schedule – PE on the beach, dinner out and a movie! The next day’s schedule held even better news – breakfast at 10 am and a few midterm prep classes followed by 2 hours of precious town time! And the following day’s sand sledding and more town time felt beyond belief.

Kate reported a luxurious 13-hour night of sleep that first night. Amelia and Dylan taught their Algebra 2 lessons as the good cop/ bad cop team-teaching duo. Ellis looked forward to runs on the beach and Sarada soaked in the ocean views. Hannah posted near the TV, watching CCN to catch up on the news. Shay used her spare time to write letters for me to deliver to family and friends. Mia characteristically made herself helpful for crews during meal time. Ra’Gene prepared for her role as Namibia’s first President, Sam Nujoma in the upcoming history midterm mock trial. While Sophia paced herself on the sand dunes – taking turns between sledding and taking photos. Millie and Abby engaged thoughtfully in a history class at a colonial statue commemorating German soldiers who helped crush a rebellion against colonial rule, citing similarities with the events of Charlottesville. It was time to rest up and prepare for midterms – a mock trial of the colonization of Namibia; a town hall meeting of stakeholders who are tasked with developing a collective group management plan for the Central Kalahari Game Reserve that is acceptable to all parties; and an analytical essay about The Poisonwood Bible. I’m excited to hear how it all turned out!

There is nothing like seeing The Traveling School in action. Your daughters are rocking their semester and embracing each new experience and challenge with open arms. You would be proud of their efforts. I cannot express how grateful we are that you chose to send your daughters to southern Africa with us. We’re only halfway through the semester, but time will start to accelerate for the girls from here on out. I hope they are able to stay present in each moment – large and small – can continue to build a strong, vibrant community of trusting young women who are open to the possibilities and lessons gained from meeting new people and traveling to new places.

Many thanks to you all who made this semester a reality for these girls!

Best, Jennifer

Reflections by Abby, 16, IL

Armpits sweating, heartbeat racing, legs shaking, I jogged through the Livingstone market with my little group. We drew the attention of passersby more than our large, female tourist group usually does, as we sprinted past, panting at full force. The comments were friendly waves from adults, “hellos” from the elderly, and high fives from the thrilled children. One man, however, asked in a sarcastic tone, “Here to do charity?” I barely made out his words as I ran past his near whisper. But as I began to contemplate his question in the following seconds, an intense wave of shame washed over me. The thought that my wish to broaden my world understanding could be viewed as an attempt to fix something I know nothing about made me question the mark our little clan leaves on the places we travel. I wished suddenly in that moment to lock myself up in our hostel for the rest of the semester, learning all I could there.

Upon thinking about this frozen moment, however, I have begun to see its value. The millions of reasons and history leading that man to his question is part of what brought me here. We live two separate lives, him and I, and though we may never understand the other, he allowed ne a brief reminder of the difference between doing something for yourself and doing something to make yourself feel better. There is no doubt that I arrived at The Traveling School with some semi-selfish intentions. I came to rethink my own perception of the world and find passion in places I didn’t expect to. And as is inevitable, the target for why I came is always moving and expanding. What I did not come here to do, as this man eventually reminded me, was come to reinforce the idea that I am a kind, perfect human who helps where it is needed. I came simply to appreciate and to learn. And as this moment so suddenly helped me to realize, no one story, on either my side or his, can ever be complete. I may never understand what affected his interaction and take on our group. In just four words, this man forced me to remember the importance of an open mind and remind me of what brought me to that moment.

My response to this man’s question holds irony that is important to address, however. Doing charity, for obvious reasons, isn’t a negative in and of itself. Taking moments to acknowledge your own privilege and help where inequities exist is necessary in fully appreciating a new environment. Doing so in the right way is essential. What stands out to me as most crucial is examining the idea previously discussed, helping to help versus helping to make yourself feel better. The only way to accomplish this is through taking the time to understand a community before spending time helping as you see fit. In taking time to listen and think about inequities in an environment new to you, you are capable of connecting and finding real ways to help where it is needed. Charity is not inherently a way to look down on people different from you, as she reminded me, it is crucial to pay close attention to the way you do so.

Academic Update

Science:

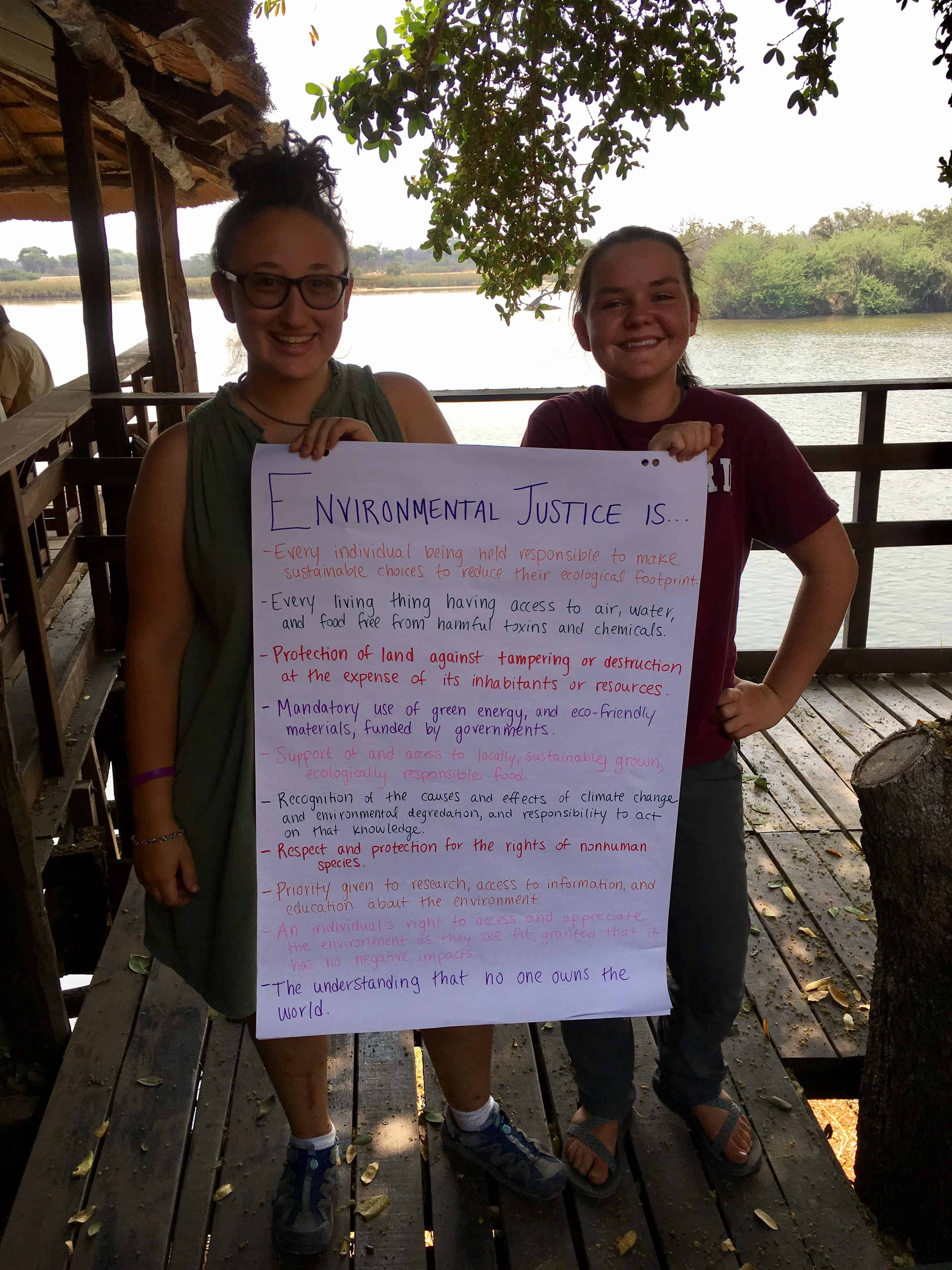

After concluding their study of elephant behavior, the students have jumped into the complex issues surrounding land and resource management, and what it means in the context of southern Africa. In conjunction with our global studies unit, they looked at the rights of indigenous people who have historically survived through a close relationship with the land they occupied. We examined the idea of environmental justice using a document drafted by leaders of First Nations in the United States. As individuals, and then as a class, the students came up with their own principles of environmental justice. With that document in mind, the class turned its focus to biodiversity and the key ecological systems that require management and protection. We examined the case study of a proposed commercial road that would cut through the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, and debated the ethical pros and cons of that project. The class has explored other issues surrounding land management, from fencing to hunting and human-wildlife conflict. The students have brought perspectives from other classes, tying in many of the themes that will continue to resurface throughout the semester. Their growing knowledge has made for lively, thoughtful discussions and debates, and has allowed them to tackle these big questions of how to manage land, people, and wildlife that do not have easy answers. Moving forward we will focus on several different models for conservation before moving into our midterm project. They will draw on their critical thinking skills to examine a multitude of interests surrounding a particular area of land and propose a management plan of their own.

Math:

In Chapter 2 of the Algebra II curriculum the students have been exploring linear functions. They are using the tools they learned in Chapter 1 to understand equations and inequalities and grow comfortable applying what they know to linear graphs. Taking turns teaching parts of each section to the class allows the girls to grapple with new information and gain a deeper understanding by sharing their knowledge with their classmates. We will finish up our current unit with a chapter test next week, before transitioning into linear systems in Chapter 3.

World Literature and Composition:

We’ve spent the past few weeks in World Literature & Composition diving deeper into The Poisonwood Bible. The students began spearheading captivating student-led discussions about assigned portions of the novel which has been an exciting opportunity for them to showcase their close reading and critical thinking. Because the novel is rife with possible discussion topics, the student-led discussions have enabled the girls to focus on the exact literary element(s) they are most passionate about and hone in on the burning questions frequently posed around meal circles like how Leah’s conceptualizations of childhood and privilege have shifted since moving to the Congo and whether or not Orleanna and Nathan’s respective parenting styles are effective. So far, the discussions have been fantastic, and they have given us ample opportunities to engage with the rich characters Kingsolver created. While doing so, the students have written two extended reading responses to help prepare them for their upcoming Analytical Essay Midterm, for which they will craft a thesis and textual evidence-driven paper in response to a prompt of their choice. Students have also been carefully crafting (and re-crafting) their “Where I’m From” poems which will be performed during the upcoming Campus Visit. During our stay at Rainbow River Lodge in Divundi, Namibia, we listened to Brene Brown’s TED Talk entitled “Power of Vulnerability” as a class and discussed both what makes us feel vulnerable and how we can add vulnerability to our final drafts. Seeing the transformations between the first draft (written during our first week in Zambia), the second draft (written a few weeks later in Botswana), and the final drafts (written after over a month of travel and learning together in Namibia) has been incredible; the girls have truly opened themselves up to vulnerability and challenged themselves to be economical in their poetry-writing. We are looking forward to continuing to examine The Poisonwood Bible this week and next, and, though the students will be sad to bid farewell to the beloved characters, they are eager to begin reading Mother to Mother as we head towards South Africa.

History and Government:

Looking at the foundations of socialist and capitalist economic systems, the class analyzed current successes, challenges and political trends in our areas of travel. We discussed the varying models that Botswana, Zambia, and Zimbabwe have taken since independence. From consolidating authoritarian rule, to providing a model democracy, we discussed the potential reasons for these trends, and the challenges that the new governments faced at the time of independence. We transitioned into our next unit on colonialism and independence. The class is currently diving into the ways that the colonial system impacted the region, and the psychology behind the justification of colonial exploitation. Engaging in thoughtful questions about the impacts of this system and associated rationale, the class is starting to apply their broader knowledge to a case study on Namibia. Looking forward, the students are all participating in a mock criminal trial as part of the midterm exam. They will be playing witnesses and attorneys, and representing the Namibian indigenous population and independence movement, as well as the German and South African occupancy during the colonial era. The class will take this opportunity to learn about the rarely discussed genocide committed by the German military during the early 1900’s, and the long road to independence, which Namibia gained in 1990. There is equal excitement to attempt to bring some of this region’s ‘bad guys’ to justice, as well as impersonate them on the witness stand.

Travel Journalism: